Archive Blog: Duckfat: The Life and Death of Edward Bradshaw

27 July 2023

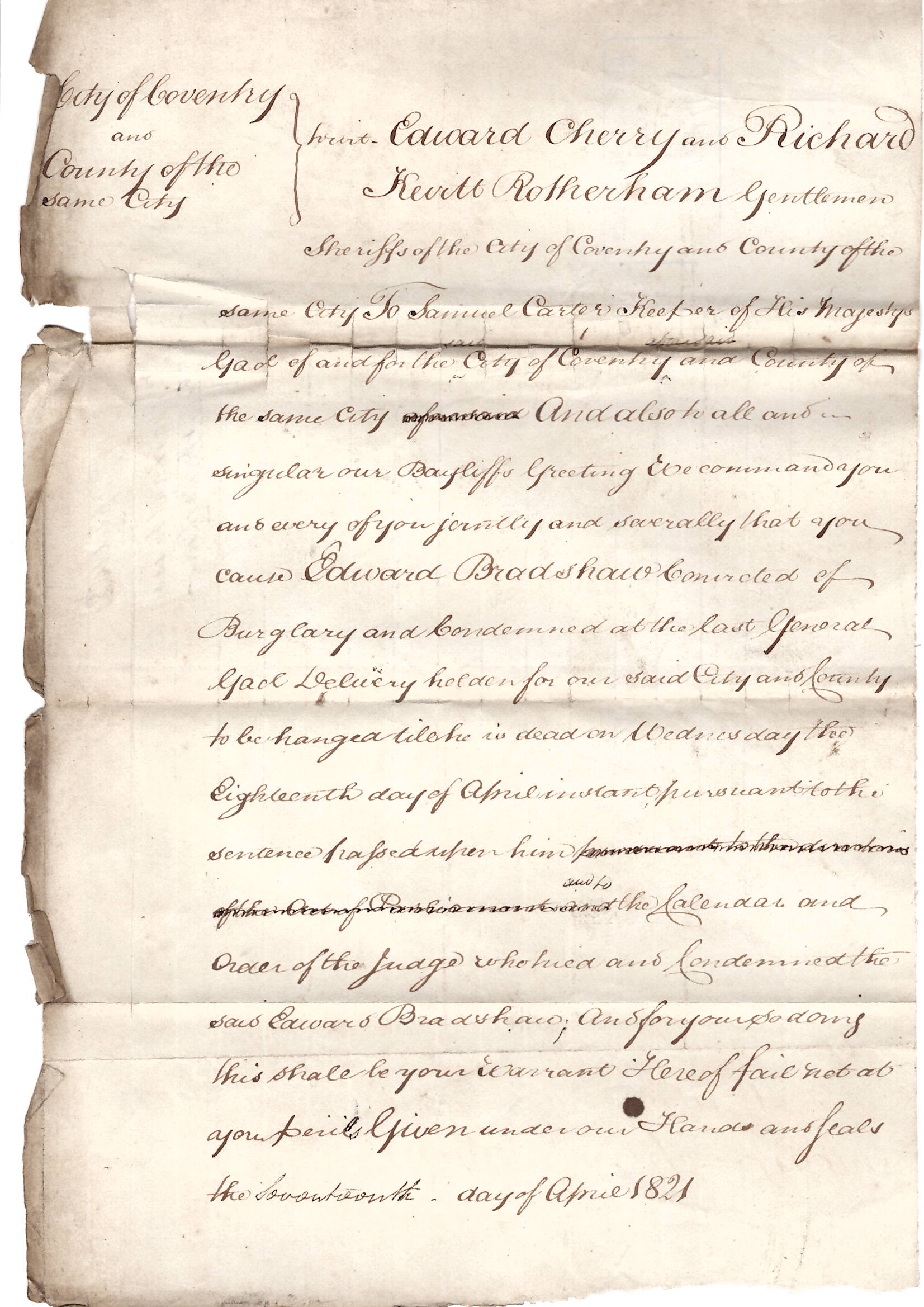

The document that accompanies this post is one of the more gruesome items in the Coventry Archives collections: it is the original execution warrant, issued against a young man by the name of Edward Bradshaw.

Image: An original execution warrant

At the top of the execution warrant are some other names. Edward Cherry and Richard Kevitt Rotherham were sherriffs of the city, and already notable men: Cherry was a coal dealer and brickmaker who had served in the Warwickshire Regiment Militia; Rotherham was well-known as a watchmaker and silk dyer. A little further down is the name of Samuel Carter, who was the gaoler at Coventry; he had been recommended to the position by a man named William Herbert, who had himself once served as a sheriff.

But the name that interests us here is that of Edward Bradshaw, who was also known by the nickname Duckfat. At the time that the warrant was issued, Bradshaw had already been in gaol for about seven months. He had been one of a group of men who had broken into the Punch Bowl public house situated at Spon End. During the course of the burglary, the landlord, Mr. Bobbett, and a close neighbour by the name of Lines, came to investigate. As the gang made their escape, Duckfat was apprehended and, in the ensuing struggle, he stabbed Lines with a knife that he later claimed in court he carried for self-defence.

Duckfat was the only member of the gang to be arrested and sent for trial.

The events that night in September 1820 formed the last chapter of a short and rather tragic life. Duckfat had been a scholar at Bablake, but upon leaving school he'd fallen in with a bad crowd and was always involved in crime of one sort or another. If he wasn't gambling on the Sabbath, he was stealing pigs and fowl or - for the short time that he was in Birmingham - dealing in and circulating "bad money." He was evidently dissatisfied with the life he was leading, however, for when he returned to Coventry, he was determined to change his ways. He found work and it was said that he had never been happier. Unfortunately, Duckfat's determination to stay on the straight and narrow wavered, and he was soon back to his criminal trangressions, having fallen in with more dubious company. His involvement in the burglary at the Punch Bowl was to be his undoing: found guilty of the crime of burglary at his trial, he was sentenced to death by hanging at Whitley Common.

Mindful of the fate that awaited him, Duckfat wrote to his compatriots whilst he was imprisoned, exhorting them to change their wicked ways. A number of religious ministers and "pious people" visited him and although it was said that he never expressed any true remorse during these visits, he was described as polite and courteous and as a result he captured the imagination of the people of Coventry, who sympathised with his plight. Even those who were responsible for him whilst he was incarcerated took pity: on several occasions Bradshaw was allowed to leave the prison on errands in the hope that he would take the opportunity to abscond. Having completed his errand, however, he would always return to the gaol.

When Bradshaw arrived at the Whitley Common gallows on 25th April 1821, reports written at the time suggested that he was more interested in the number of people who had turned out to witness his execution than in the Bible that Ministers had placed in his hands. But after a psalm had been sung and a prayer offered, Bradshaw asked if he could address the assembled throng: he announced that he was guilty of the crime for which he had been convicted, and not only acknowledged the justice of the sentence that he had been given, but also hoped that his execution might serve as an object lesson in the "awful consequences of keeping bad company." The general sense of sympathy for Bradshaw - as well as the fact that his execution was the first to have happened in the city for over twenty years- might have accounted for the size of the crowd that assembled to witness the event: estimates range from between fifteen and twenty thousand people. Once the formalities had been completed, Bradshaw was hanged: " a few minutes before 12 o'clock," a published broadside states, "the platform fell...(and) a few convulsions terminated his earthly career." Bradshaw was later buried in the new churchyard at St Michael's. He was eighteen at the time of his death.

Article created by Coventry Archives.